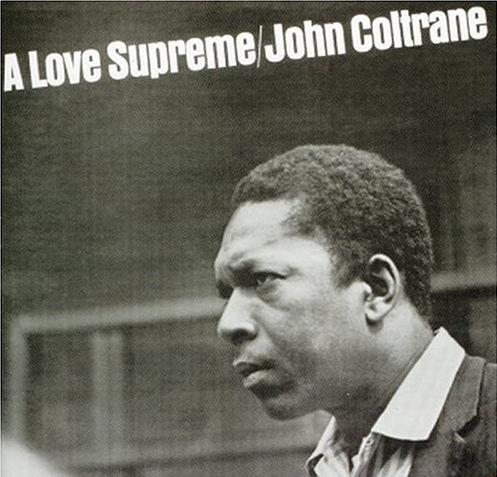

1/20/11 – A Love Supreme (John Coltrane)

All Praise Be To God To Whom All Praise Is Due.

- John Coltrane

Early in my musical experience, I remember taking on an assignment/project from my first piano teacher to assemble a musical scrapbook, surveying a wide variety of musical styles, from rap to metal, classical to jazz, contemporary Christian to country. (Unfortunately, I believe it was lost/thrown out/destroyed in one of a few subsequent moves since leaving home.) Oddly enough, similar in some ways to this blog project in that I was encouraged to increase my exposure to styles otherwise foreign to me at the time and look critically at each. And I hated jazz. It seemed to me at the age of 8 to be a musical mess; a bunch of random notes and phrases that weren’t melodic enough to sing to, clusters of notes way beyond my comprehension or palate at that time, and a lack of form and structure.

While I have grown an appreciation for the jazz idiom since, listening to A Love Supreme, I question if this was one of the albums I looked at twentysome years ago. Combining elements of bebop and free jazz, I start to take the same view I did back all those years. The blazing saxophone melodies are an impressing display of virtuosity, but still feel like they’re often lacking in lyricism. The modal harmonies I grasp moreso now, but “free jazz” I think left a bad taste in my mouth those many years ago that I still haven’t gotten rid of.

However, the more I listen to this album, the more I get it. The latin-ish groove of the opening “I. Acknowledgement” giving way to the mantra of “a love supreme” are a less than subtle hint toward the influence of Coltrane’s faith. (Interestingly enough, the saxophonist was beatified in the African Orthodox Church in 1971… that’s Saint John Coltrane to you…) The idea of structuring a 7+ minute track around a four-note fragment of a melody still doesn’t feel like enough of a composed form to me, but the sheer ability to spin so much out of that basic motif is impressive in it’s own right. Conceptually. In practice, I still don’t feel it. Maybe after a dozen more listens or so.

“II. Resolution” has a bit more melodically going for it, and likewise, it grows on me the more I listen to it. Jimmy Garrison sets a nice tone with the bass introduction to this second movement. Again, the modal harmonies sound a little clunky and heavy-handed at times, but they aren’t as jarring as I believe they seemed to my younger self. McCoy Tyner’s stylings on piano come to the forefront moreso here, and fall into that middle ground in between what I like and what I merely appreciate.

“III. Persuance” shares the love with an extended drum introduction by Elvin Jones before digging into the head of the form. (Does the term “head” really still apply here? I mean, if there’s no straightforward return to the material later on is it still a theme? Oh, the philosophy of music…) I think it’s still the lack of form that throws me for a loop here. Everywhere else in music, there’s a sense of departure and return. In pop music, there’s verses (departures) and choruses (returns.) In classical music, there’s an exposition (statement of main theme) development (departure,) and a recapitulation (or returning.) Even in most textbook jazz, there’s a head (theme,) solos (departures,) and a head out (a return to the head.) Free jazz seems to want to move linearly, not cyclically. There’s no return more often than not, and as such, no sense of completion and closure. While eight minutes into this track or movement, the bass begins to restate the 4-note motif from the opening section, it doesn’t feel substantial enough to be a return to home, so to speak.

The final track/movement, “IV. Psalm,” oddly enough begins to feel like a return at last. The opening is texturally the same feeling as the intro to the beginning, with it’s washy cymbals and gong. The saxophone obbligato is more triadic than quartal, making it seem strangely more familiar than the opening it is referencing. This time however, there is no groove – the quartet stays out of time, in a meditative state of fluid harmonies.

I find it personally difficult to be critical of this album. There’s a sort of pressure listening to supposedly great music to agree with that assessment. Therefore, I question what everyone else sees and places upon a pedestal that I’m not getting. This recording is one of the hallmarks of jazz history, and I don’t get why, neither analytically nor aesthetically. I really wish I did. I don’t assume to take the position that the Emperor has no clothes, because there are too many people whose opinions and assessments of music of quality I respect who revere this work. Maybe in another twenty years, I’ll look back at this the same way I think back on that scrapbook; with a newfound appreciation of some things, and tastes that may change (or dare I say, grow,) over time.

Tomorrow – The Near Demise of the High Wire Dancer (Antje Duvekot)

Next week – Light as a Feather (Chick Corea)

Shawn,

ReplyDeleteWow, great blog! You're really putting a lot of work into your posts and it shows. It took me a few months to start getting more website traffic. It helps to connect with other bloggers out there. Keep it up and great work! :)

I shared your link on my facebook page.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comments - I'm glad you enjoy it!

ReplyDelete